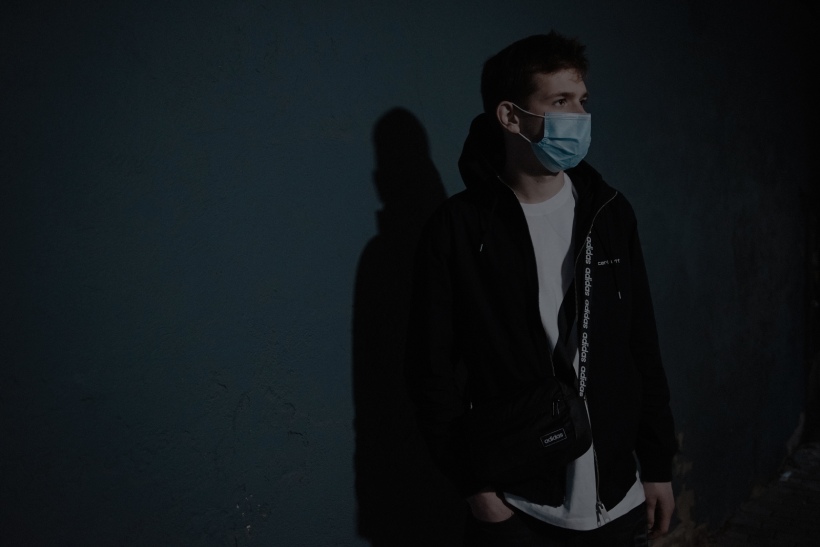

Torture and abuse in 2020 – story of Maksim M.

19 years old, student. “I was not afraid, I thought that whatever was going to happen would happen anyway. But all this was definitely a shock.”

Maksim tells a detailed story of his arrest and detention for the first time and admits he does not remember everything. For instance, he can’t remember what he was fed or exactly how many days he spent in Zhodzina. He also says that in August he chose to abstain from voting in the first presidential election in his life: he was certain that his vote would not change anything. But after what he had witnessed in the Akrestsina and Zhodzina detention centers, he realized he would not fail to vote in the next elections. In 2020 he developed a strong sense of civic duty and responsibility.

“I jokingly said to my friends: ‘Let’s go take a look at avtozaks.’ And lo and behold – a prisoner transporter is pulling up, and everybody is running away”

“It’s like a GTA game, I’m standing against the wall and getting kicked in the legs”

“On the eve of the presidential election, I came to Minsk from Mahiliou to visit a friend. I wanted to buy a couple of things. On August 9, the three of us went to the mall across from the Sports Palace; at around 9 pm people gathered there and started expressing their indignation at the fact that ‘he [Lukashenko] had fraudulently claimed so many votes for himself’. I jokingly said to my friends: ‘Let’s go take a look at avtozaks [police trucks for transporting detainees].’ And at some point, everyone went out onto the roadway… And lo and behold – a prisoner transporter is pulling up, and everybody is running away. When I heard the first stun grenade, I felt my heart drop. I thought: ‘Holy sh*t, it’s a war.’ The adrenaline kicked in, I ran and called a friend on the fly and asked to let my parents know what was happening in case I didn’t get in touch the next day.

We had gotten bored of running by 2–3 am, so we went to a night store on Masherau Avenue. Then, we were leaving the store, and there was a riot police (OMON) squad 15 meters to the left. When we were running, it was scary. But I didn’t even think they could pursue us. We walked in circles around Belaya Vezha for a while, and then sat down in a courtyard and smoked. And then the riot police came running in, flashlights on: ‘Working, working! Hands! Get down! Aaaagh! Working!’

It was like a GTA game, I was standing against the wall and getting kicked in the legs. Then they took me under the arm and led me to a prisoner transporter, where a riot policeman was standing. ‘Come on, you bitches!’ – and I was kicked in the chest. We were practically standing on top of each other in a tall box in the prisoner transport vehicle, it was impossible to breathe, and sweat was dripping. We were being transported. But where to? We could only hear the sound of stones thrown at the prisoner transporters. I was not afraid, I thought that whatever was going to happen would happen anyway. But all this was definitely a shock.”

We were brought to our knees against the wall. When they told us to move, I saw blood and some money on the floor. What the hell was going on?!

“There was a commotion and yelling in the hallway at Akrestsina: ‘Lower! Lower!’ We were brought to our knees against the wall. When they told us to move, I saw blood and some money on the floor. What the hell was going on?! And that anecdote with the hoodie drawstring was like something from a play. I was punched in the back and heard a voice in my ear: ‘Laces off!’ I didn’t manage to pull the hoodie string out. A riot policeman came up to me and said very respectfully: ‘You can’t do it, can you?’ I don’t know if this whole situation could be called respectful, but he didn’t yell at me. And I considered this respectful. The drawstring was cut off with scissors in the end.”

“If you f*ck with us, it’ll be a bucket of sh*t next time”

“After the inspection, they started taking us away. And we heard again: ‘Down the corridor! Straight ahead! Straight ahead! Straight ahead! Lower! Lower, bitches!’ I crashed into a riot police officer in the hallway. ‘Are you f*cking kidding me?’ – and I got punched in the gut. I recall this incident with laughter now, but it was no laughing matter at the time. The guys and I were placed in a cell at the very end of the corridor. There were 32 people in it on the last night I spent there.

He asked them not to beat him, he was like: “Hey, muzhiks!” They said: “Muzhiks are in the field!” “But I have served!” “Only dogs serve!” they replied and beat him to a pulp…

When the detainees were marked on August 10–11, they squealed like stuck pigs. We took note of how long they were standing there against the wall, we heard those who were outside the offender detention center. The guards didn’t touch us, but there was a women’s cell across the corridor. A pregnant detainee had a bout of hyperemesis gravidarum, and her cellmates started calling for a doctor. They were given several warnings, and in the end, a riot policeman poured a bucket of chlorine solution on them. ‘If you f*ck with us, it’ll be a bucket of sh*t next time.’ They also took a man away because he was asking for food, I think. He asked them not to beat him, and he was like: ‘Hey, muzhiks [the Russian word ‘muzhik’ originally means a man belonging to peasantry; however, being called a ‘(real) muzhik’ can be considered a compliment as this expression is often used to refer to a courageous and decisive person willing to do anything in their power to protect and provide for their family and homeland]!’ They said: ‘Muzhiks are in the field!’ He then added: ‘I have served [in the military and/or police]!’ ‘Only dogs serve!’ they replied and beat him to a pulp…

What a joy it was when they started taking us out to the corridor on the third day. We could only get a bit of fresh air in the cell when new detainees were brought in. All in all, it was sheer bliss. All that oxygen made me dizzy. I felt unwell that night. It felt as if I had a 39C fever. I lay down on the nightstands by the window and fell asleep for the first time. I started having chills in the middle of the night, and they opened the cell door for us. ‘Have some fresh air, guys.’ And I was feeling so ill! It’s a good thing I got better in the morning – they started bringing us to trial.”

“Before the trial, I asked a middle-aged policewoman in the offender detention center courtyard: ‘Please tell me what’s going on out there.’ She advised me to plead guilty as in this case I might only be fined. I don’t know if she was lying. But all those who had pleaded not guilty ended up being detained for days. I felt she still had some knowledge to share. She said my judge was good. And I kind of decided to take her advice but didn’t agree with the claim that I had been detained at 9 pm. That’s not how it went down!

I got 15 days of detention. I said ‘Thank you’ and walked out. They gave us porridge with sausages in the temporary detention center in the evening. Pure bliss! I even took a nap: a guy gave up his space on a bunk bed. I saw Dzimon, one of my friends, before leaving for Zhodzina. The other friend of ours stayed in the offender detention center and was then moved to Slutsk [a city in Belarus located about 100 kilometers south of Minsk]. A riot policeman was standing in front of a prisoner transporter, he was picking a fight with everyone and hitting people with his truncheon. He hit me in the buttocks.

The ride wasn’t that tough, riot policemen even talked to us. One of them tapped me on the shoulder: ‘How old are you?’ I said: ‘I’m 18.’ ‘Still just a kid. I wouldn’t want to be in such a place if I were your age.’ And when we arrived in Zhodzina and were led away, he added: ‘Guys, take care of the kid.’

When I was still in the temporary detention center, I wrote my dad’s phone number with a pencil on toilet paper and hoped that I would be able to give it to someone. As I was getting off the prisoner transporter, I left this piece of paper on the seat. I don’t know what happened next. Dad later told me that a lot of people were already calling him at the time.”

Just your regular “Belarusian drug addicts and drunks” were in the cell with us: IT professionals and entrepreneurs

“Dzimon and I entered a prison cell and heard ‘Guys, help yourselves to some bread!’ right away. It was so cool! I made my bed on the floor and took a nap. It was unclear what was going on and what would happen later. We started exercising in the cell and made chess pieces out of bread. Just your regular ‘Belarusian drug addicts and drunks’ were in the cell with us: IT professionals and entrepreneurs.

“Bro, this hoodie saved my life!”

After we had been led out of the cell on the second day, I came back without Dzimon. I was about to go to sleep when the door opened: ‘Maksimau, out!’ Wow! I stood up against the wall, turned my head, and saw a guy wearing my hoodie, the one I left in the offender detention center. ‘That’s my hoodie!’ ‘I know, bro, it saved my life!’

We left the facility together, there were so many people around – I was shocked! We were given rations and laces right away, and… my dad was standing there! My name was on the detainee list in Mahiliou, and my father spent the night next to the temporary detention center there and went to Minsk and Zhodzina later. He cast his vote for Lukashenko, by the way. But I think his opinion changed after what had transpired.”

“At the end of October, I started getting calls from a police office: they wanted me to come to a meeting with them. I postponed this for as long as I could. I told them I was sick and slept over at a friend’s house. An acquaintance of mine who had left Belarus gave me the contact info for the Dapamoga foundation. Dapamoga representatives told me that I had to flee: security forces wouldn’t leave me alone. I lied to my parents about visiting a friend in Minsk, and I only brought one backpack with me. I managed to hitchhike to the border. I was afraid I wouldn’t be let out of Belarus and let into Lithuania without a visa, but the foundation helped. Only at the Belarus-Lithuania border did I call my mom. She didn’t believe me at once, but she now seems to have made peace with my moving abroad. She says it’s better than being in prison.”

Maksim is now working in medical mask manufacturing and renting an apartment with other Belarusians who were forced to leave the country in a hurry. He’d like to continue his education, but he does not have a high school diploma. Maksim says that as he was a community college student, he only has a high school graduation certificate, which “does not count for anything anywhere”. If you’d like to support Maksim, you can order his handmade wall clocks featuring the Pahonia coat of arms here.

P.S. Maksim has not filed a claim with the Investigative Committee of Belarus.

Author: August2020 project team

Photo: August2020 project team