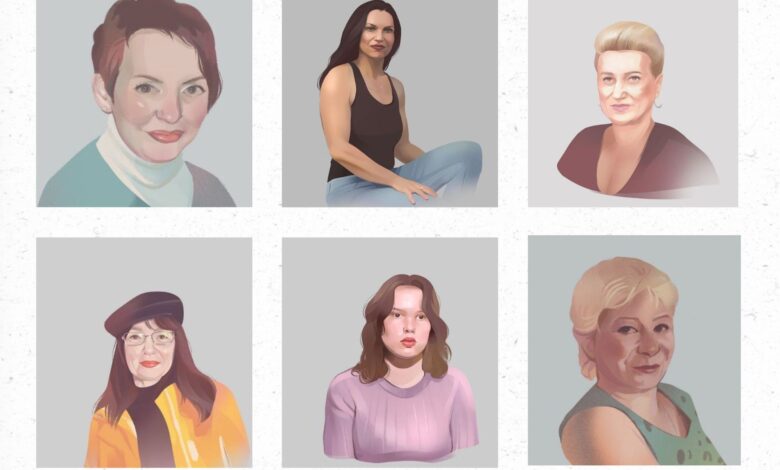

Women political prisoners of Belarus through prism of art

On the eve of International Women’s Day, celebrated on March 8, Belarusian human rights activists called on the public to support women who have actively participated in the fight for freedom in Belarus, for which they are subjected to repression to this day. The Politvyazynka project representatives tell the Voice of Belarus about Belarusian women political prisoners: the initiative posts their portraits and stories of their lives before and after imprisonment so that the society does not forget about the repressed in Belarus against the backdrop of the war in Ukraine.

Volha Mayorava, 56, is a Belarusian female political prisoner who was handed the longest prison sentence: she’s received 20 years in a penal colony. The youngest political prisoner is 18-year-old Anita Bakunovich. It is not uncommon for entire families to end up in prison: a mother and her daughter, a father and his son; sometimes, the whole family is sentenced to imprisonment.

Sviatlana Baranouskaya and her daughter had spent four months in so-called Valadarka – a pre-trial detention center on Valadarskaha Street in Minsk. They saw each other only once when they were brought there as they stood next to each other facing the wall in the prison yard.

“Also, my Anastasiya helped me carry a mattress because my strength left me at that moment. The mattress was very bad, and I cried and said I wouldn’t make it to the cell. The prison’s green corridors smelled of mud and ground and had a foul stench overall,” says Sviatlana. The women were placed in adjacent cells. “I can honestly say that being near her gave me a warm feeling in my heart,” reminisces Sviatlana.

Those who served time in Valadarka know of the term “Radio Valadarka”: it is a way of communicating when one shouts out the window and thus talks with people from other prison cells. “It was my daughter’s birthday. I spoke words of love and adoration to her through the window. It seemed that everyone was listening to me only,” says Sviatlana.

Sviatlana and her daughter served time in the pre-trial detention center until their trial. They were sentenced to three years of home confinement with penal labor each. Sviatlana left Belarus after the trial. She crossed the border walking through a swamp in subzero temperatures and waist-deep in water. Her daughter Anastasiya decided to stay in Belarus. Sviatlana confesses that she is highly distressed about what could happen to her daughter, grandson, and husband.

The Politvyazynka project was created by journalist Yauheniya Douhaya, artist Hanna Tatur, and a few other people. Yauheniya had to flee Belarus for Ukraine due to persecution in 2020. After the start of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, she moved to Poland, where she has been involved in activism and human rights defense.

Belarusian women now find themselves in a situation where their suffering is invalidated with the explanation that men are more likely to be physically abused by security forces. Yet, women also get beaten and face extreme psychological pressure and threats to the well-being of their children, among other things.

Ina Shyrokaya is a mother of five children. In August 2020, riot police beat her 18-year-old son for participating in a peaceful protest while her daughter was volunteering on Akrestina Street. Then Ina started attending protest rallies and actively expressing her stance at work: she was a manager in one of Hrodna’s coffee shops. On the evening before Lukashenko’s visit to Hrodna, Ina placed white and red candles on the porch of the coffee house. She was fired after that. Then, one morning she was detained while her three minor children were left at home. Belarusian siloviki blackmailed Ina about her children’s fate: they threatened that her older children would be imprisoned while the younger ones would be taken to an orphanage.

Ina Shyrokaya calls prison life simple and miserable:

“I learned how to sleep while pretending not to sleep, how to eat food I would never have touched before, how to catch lice and bedbugs without shuddering in disgust, how to not comb my hair for a week between showers, how to make do without clocks because time inside prison is irrelevant, and how to boil water in a mug or wash basin without getting electrocuted or, at least, not too electrocuted… I learned how to wash my private parts with a mug in one minute because there would be a waiting line for the toilet, how to make a salad in a bag and borscht from dry beets (by adding dry beets to the ‘almost-borscht’ we used to be given for lunch), how to make fish pate from ‘graves’ (that’s what we used to call unskinned boiled blue whiting they gave us three times a week), and how to store food in a shared container by filling up the space between the items with cold water bottles. I had to learn many other pointless things that would never come in handy.”

“I learned how to remove handcuffs in a prisoner transporter vehicle and to prop my feet against the walls of a tall box so that I wouldn’t get thrown around as the vehicle moved. I learned how to report at roll call and make the bed properly. I learned how to hide a water bottle on my person to pour water on the dust in the prison yard before a walk because my cellmate Volha Halubovich had asthma and experienced breathing difficulties,” says Ina.

Ina had spent more than three months in the detention center, after which she was sentenced to three years of home confinement with penal labor. She found a way to leave Belarus, but not all families manage to do that. For example, political prisoner Alena Maushuk, sentenced to six years of imprisonment, was deprived of child custody and parental rights. A former inmate has recently talked about how prison staff abused Alena:

“You can’t imagine what they are doing to her there. They deprived her of parental rights in the penal colony, and she gets placed in solitary confinement for the slightest regime offenses. They just smile at us and do what they want. It’s scary! It is horrifying! It is emotionally taxing, and for them, all means are fair in an attempt to ‘break’ someone.”

The Politvyazynka project strives to do its best so that people would not forget those heroes who fought for changes for the sake of the future of Belarus. We, in our turn, will try our best to inform you of such projects and tell you about what Belarusian women have experienced on their way to our common freedom.