“Polish border guards didn’t want to let us in”: How Belarusians become refugees twice over

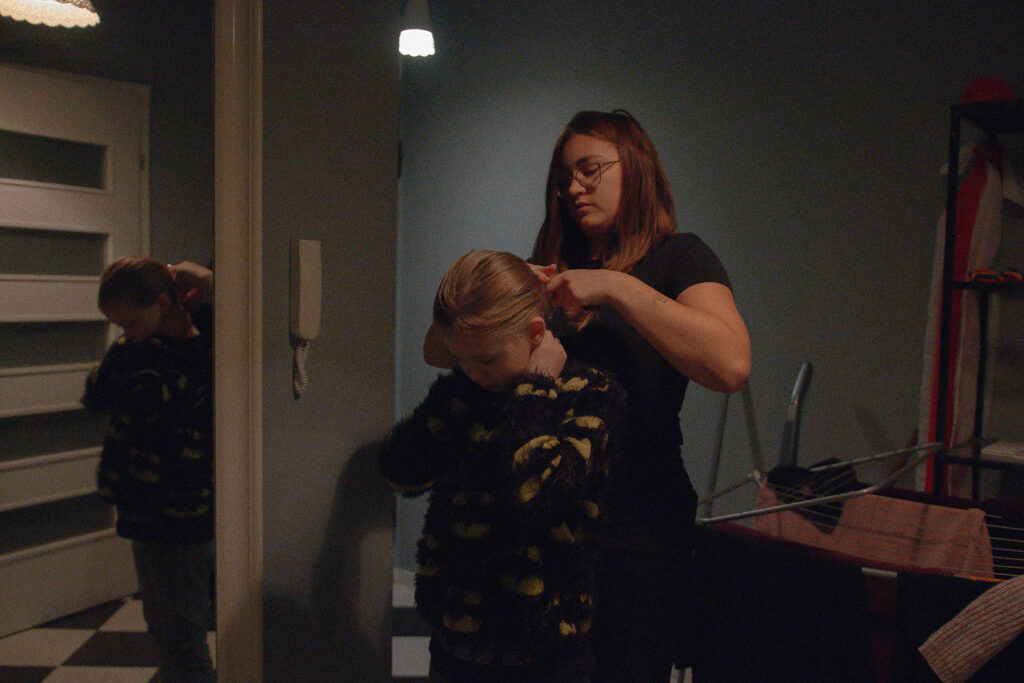

Aksana Dabryyanets and her daughter Valeryia hail from the small Belarusian town of Stolin. In 2021, they had to flee from the repression of the Belarusian regime to Ukraine. The August2020 initiative has covered the story of Aksana’s persecution. After the Russia-Ukraine war began, staying in Ukraine became dangerous, and they had to flee again into the unknown. Now the little family is trying to make ends meet in Warsaw.

Aksana was the only person in Stolin collecting signatures for Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya’s nomination as a presidential candidate in 2020. In February 2021, security forces visited Aksana’s home:

The search lasted five hours. They interrogated me, went through my personal belongings, and forcibly took my phone from me. But the time when I was truly scared was when child protection social workers came to my home the next day. My daughter is the person dearest to me. I panicked. I messaged my friends and acquaintances and started packing up. My daughter and I left for Minsk a few hours later. While we were driving, we had two traffic accidents: first, we landed in a ditch, and then another vehicle crashed into our car as it was pulling out of the ditch. Strangely enough, we didn’t take this as something terrible at the time. We were all on edge, we just waited for the traffic police and drove on.

The day after she arrived in Ukraine, Aksana received a call from her lawyer who said that an administrative case had been opened against her and that she was supposed to be detained.

“I suffered from depression in Kyiv. It was a little easier for my daughter: she had school and friends, and I stayed home alone. We loved Ukraine and decided that we would stay in Kyiv until the repression in Belarus ceased. I can’t say that I felt super safe, but Ukraine was our country to live in: there was no language barrier, we were granted legal status with no hassle, and we faced no discrimination.”

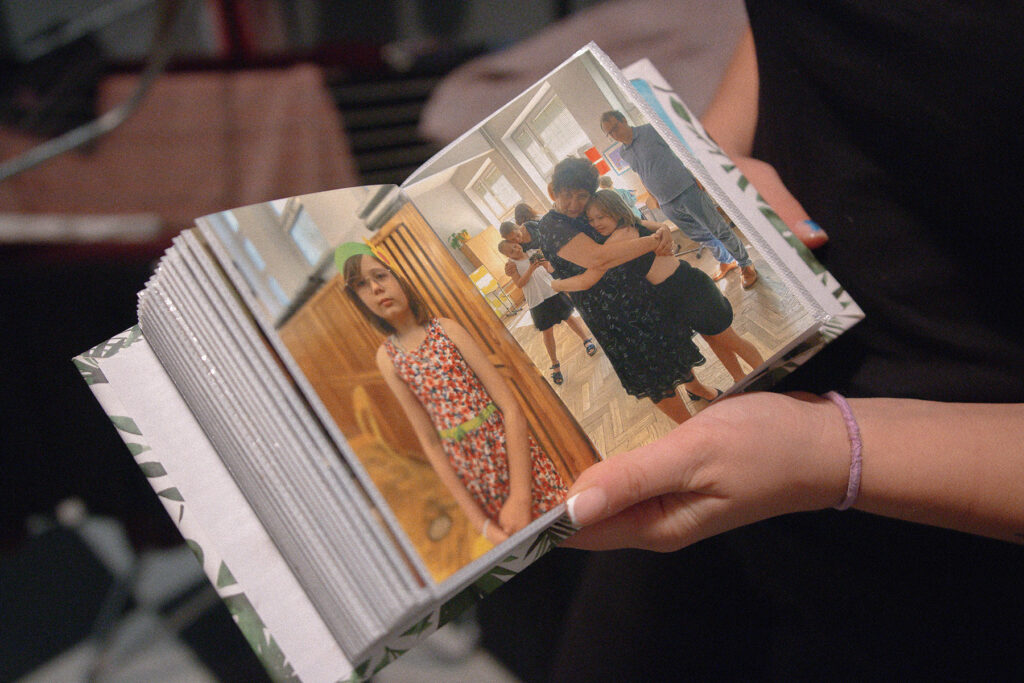

The stickers Aksana makes for the Kids in Migration project.

The stickers Aksana makes for the Kids in Migration project. In the right photo, Valeryia is hugging her Polish teacher.

In the right photo, Valeryia is hugging her Polish teacher.

“When the war began, we had lived in Kyiv for exactly one year. In Ukraine, I was involved in journalism and started working on my project about childhood in emigration. I was studying a lot and honing my professional skills in the relevant areas of expertise. But all this suddenly fell through…”

Aksana says that she knew the war was coming because she followed the news:

“All my friends said that Putin only wanted to scare people and that we should be more coolheaded and optimistic. But I was aware of what the Russian regime was capable of, so I tried to prepare for what was to come. Anxiety was growing all the time. Two evacuations at my daughters’ school threw me out of whack. The first evacuation was for training purposes, and the other was due to a false bomb alert.”

“After the evacuations, I had a nervous breakdown. The thought of an evacuation happening for real was terrifying. I cried and worried a lot. On February 23, when we went to bed, I told Valeryia that I would start stocking up on water and food supplies the following day and that we would probably have to sleep in the bathtub because the bomb shelter was far away. Valeryia got frightened and cried.”

I woke up in the morning, opened Instagram, and saw terrible news:

I told everyone I knew: if a war broke out, I would not be at a loss, I would pack up quickly and take a train to somewhere safe. This turned out to be an unrealistic scenario. I searched the Internet for every possible option out there and tried to buy some tickets. Eventually, I found out there was an evacuation trip arranged by the Free Belarus Center and decided to leave with them. We spent a lot of time waiting for a bus. The bus couldn’t even get into the city due to huge traffic jams, and the trip was canceled. The husband of the Free Belarus Center’s founder was on his way to Rivne and had three vacant seats in his car. It was a collective decision to evacuate my daughter, myself, and a young man who had trouble walking after a leg surgery from Kyiv.

“In Rivne, we found a car that took us to the vicinity of the nearest border crossing point. There was a huge line at the Ukraine-Poland border. We walked more than 15 kilometers to get to the border crossing point. Valeryia had a nosebleed due to overexertion. I was worried that if I had to call an ambulance, the ambulance vehicle would be unable to get there.

A huge crowd of foreigners and women with children was waiting near the border crossing point. To keep my daughter warm, I took off my sweater and put it on her, while I stayed in my jacket and top. We waited a long time to be let through. It was freezing cold. I couldn’t stand this anymore and unzipped my jacket in front of a border guard, showed him what I was wearing, and showed him my daughter wrapped in all the T-shirts and sweaters. Only then did they feel sorry for us and allow us to proceed to the border crossing.

We crossed the Ukrainian border easily enough, but Polish border guards didn’t want to let us in for a long time: I had to be questioned.”

Aksana says that it was easier for her in Poland at first. The realization that they were lucky kept her afloat: they crossed the border relatively easily and set up a generally okay life in Poland.

I used to compare myself to people around me and didn’t pay attention to my emotions. How can I be worried about myself if Ukraine is being bombed this very moment? It was only in summer that I realized: it was super hard for me in Poland.

“I have received international protection and work as a nail technician now. I don’t get home until 10 pm or midnight, and my daughter stays home alone. I earn enough money to pay rent and buy groceries only, and I rarely have days off: today is the first one in two weeks.”

Aksana says she makes no plans for the future.

“I wanted to continue my education but realized that I couldn’t juggle the demands of both work and school. Right now, I am working for us just to get by. I certainly would like to return to Belarus, but I don’t believe this can happen any time soon.”