“A busload of Ukrainian women defended me”: Artsiom’s story of being refugee twice over

Thousands of Belarusians, forced to flee the Lukashenko regime’s repression and find a new home in Ukraine, became refugees for the second time because of the Russia-Ukraine war. Many of them took shelter in Poland. Together with the August2020 initiative, we tell stories of such “double” refugees.

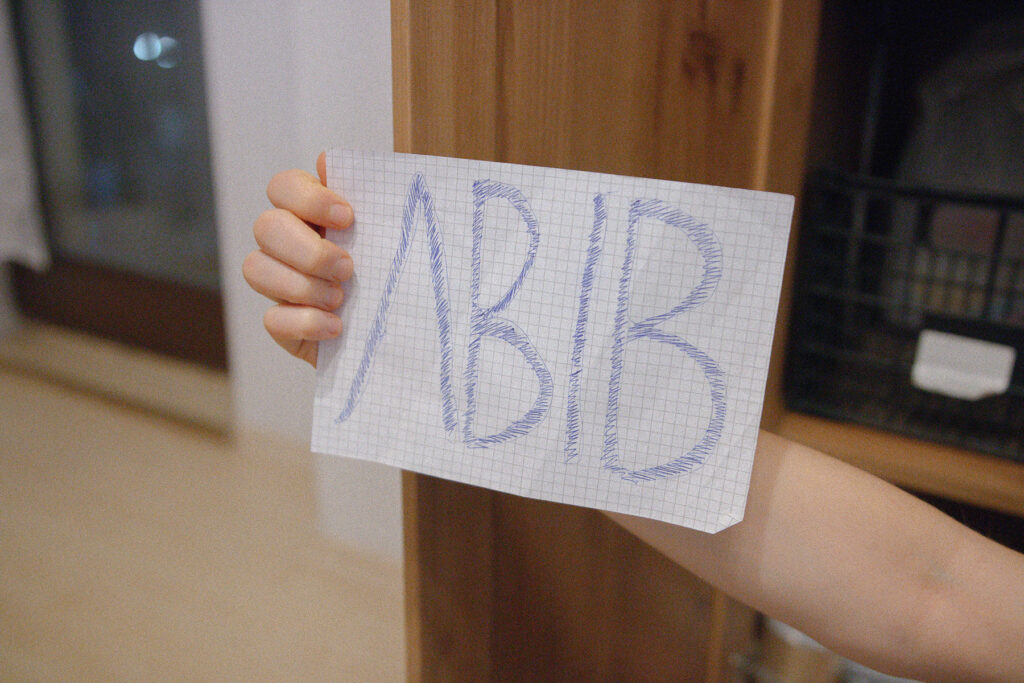

Artsiom (not his real name) admits that he is afraid to tell the story of what caused his departure from Belarus in detail. He only mentions that he was immersed in queer activism.

“I hadn’t felt safe in Minsk for the last few months and faced an emotional low point. I decided to move to Kyiv after my friends had been detained and my apartment searched. I missed Minsk, but this feeling was nowhere near comparable to the stress I’d experienced in my last months in Belarus when feelings of personal insecurity were intertwined with problems in my personal life. My life in Ukraine was serene and easy compared to those last months in Belarus. Sometimes I even joked, ‘Thanks to cops for ending my misery and making me move.'”

“Adapting to life in Ukraine was not very difficult. Thanks to my acquaintances, I found a place to live, a circle of people to communicate with, and established connections within the local community through people who had arrived before me. I joined local activism work, and there wasn’t much strife and immigrant depression.”

Artsiom had lived in Kyiv for six months. He says he was preparing for war. He met the news of bombings in the relatively safe city of Lviv:

“I thought the war would begin on February 15, so on February 14, I took the things I could carry and left Kyiv for Lviv. When a friend woke me up at 5 am on February 24 and told me to evacuate to Warsaw as soon as possible, I even felt angry because I thought the war started two days earlier when the gun battles in Donetsk intensified. After half an hour, I got a little worried, bought the tickets, and spent the rest of the day in chat rooms looking for information for my friends on how to leave Ukraine.”

“In Lviv, I wasn’t that afraid for my life, and I felt that I should rather help others than just run away. My hands were trembling with exertion by the end of the day, and I took care of my departure plans the next day. The war did not start abruptly for me, but it was still very stressful.”

Artsiom says that getting to Warsaw was not as easy as he thought:

“I felt like a fool for being unable to find a way out of Lviv. On February 25, my friends panicked and talked me into hitchhiking to the border. Then we walked all night to the border crossing point. I was walking in the company of a Nigerian family and tried to cheer them up because they were terrified, completely disoriented, and didn’t understand what was going on.”

“When I got to the border at around 7 am, no one was allowed to cross it: only buses with women and small children would depart once an hour. I stood next to the checkpoint until 4 pm. By then, I had spent two days outside, terribly cold and exhausted. I decided to return to Lviv and try to cross the border by bus on February 27.”

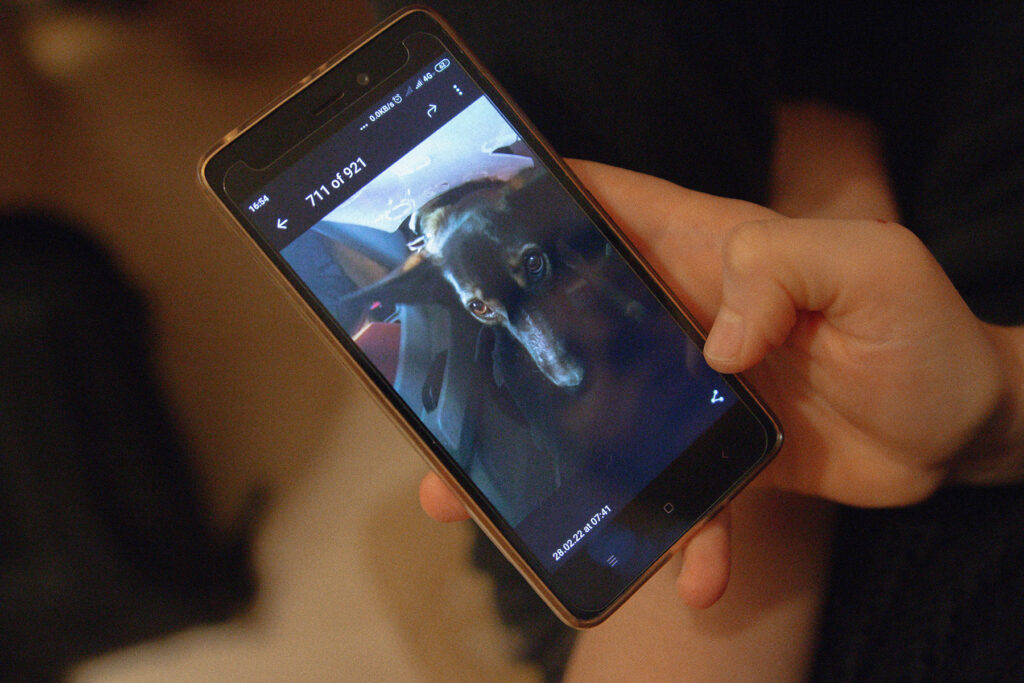

“The bus was crowded, but at least it wasn’t cold. I didn’t feel well because I had been walking around with 30-kilogram bags for two days and hadn’t slept or eaten. I felt nauseous all along. The bus was picking up women along the way, and I gave up my seat and slept on the floor. They gave me an emesis bag and tried to feed me. I was a little worried when they took my passport for inspection because I am from Belarus and all that… But Ukrainian women on the bus defended me: ‘He is just a boy! What are you trying to find in his passport?!’ There was also a dog on the bus whom I cuddled with all the time.”

Artsiom had couch surfed for the first three months in Warsaw:

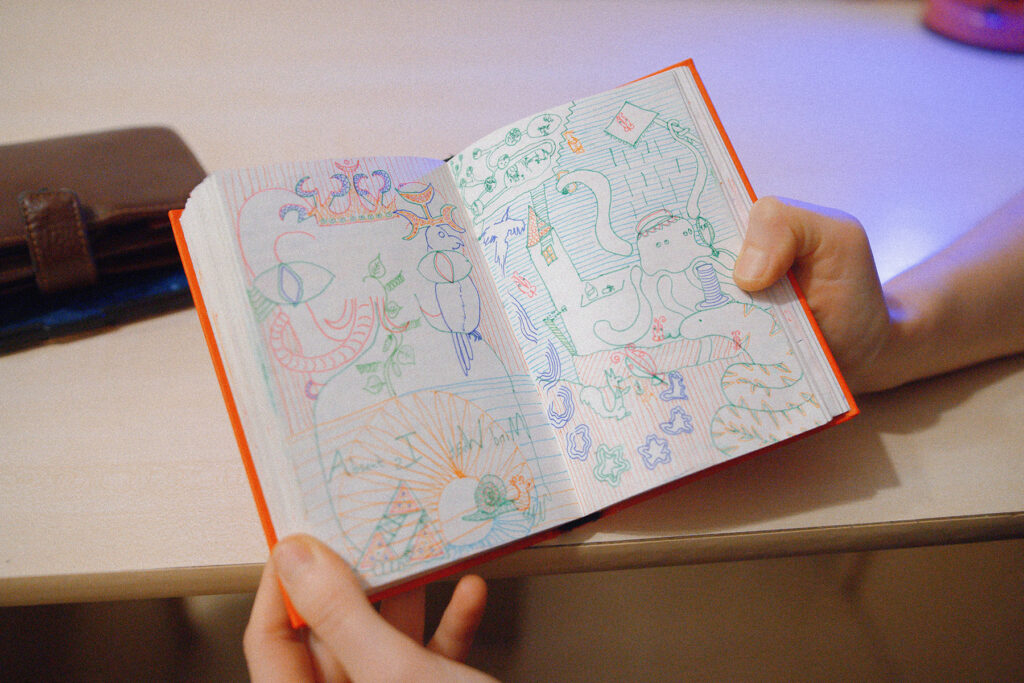

“I had lived in eight different apartments. My friends helped me find a job and financial support. I got involved in volunteering, felt important and needed, could channel all my anxiety into action, and felt comfortable in my new surroundings in the spring.”

“It got worse in the summer because the volunteering program was over, and I had time on my hands to think. I started realizing that life in Warsaw was much more complicated than in Kyiv: the language was incomprehensible, and I had to pay three times as much for my apartment. I constantly felt like a dumb immigrant who couldn’t explain anything.” Artsiom’s friends helped him find a therapist.

“My living conditions gradually improved: I am now at a more pleasant level of domestic comfort than before. I’ve dealt with the legalization issues: I applied for a residence permit, purchased an insurance policy, and received a PESEL (a national identification number used in Poland).”

Artsiom admits that he now tries not to read the news so as not to be further traumatized:

“I am stunned by the horrors that are happening in Belarus. I no longer experience emotions at the news: I don’t feel sad or cry. I just feel a dull nagging pain.”

“I don’t think I will go back to Belarus anytime soon. I certainly would’ve loved to, but I don’t make plans to not get my hopes up in vain.”