Belarusians’ struggle to save their language despite discrimination

Why are Belarusian speakers faced with daily discrimination in their home country, ranging from verbal abuse to arrests? Can Belarusian be saved in spite of systemic discrimination? The new film by Voice of Belarus, Malanka Media and Human Rights Center Viasna examines the challenges and complexities surrounding the use of Belarusian in Belarus.

There have been many peoples, which first lost their language… and then they perished entirely. So do not abandon our Belarusian language, lest we perish!

From the Preface to ‘Belarusian Flute’ by Francišak Bahuševič (1891)

Each year, Radio Svaboda, a prominent broadcaster, holds an online vote where the audience gets to choose the Belarusian Word of the Year. In 2023, mova emerged as the clear favorite. Many Belarusians use this word, simply meaning “the language”, to refer to their native tongue. It is obvious that Belarusians recognize the pivotal role that their mother tongue plays in shaping their identity and future.

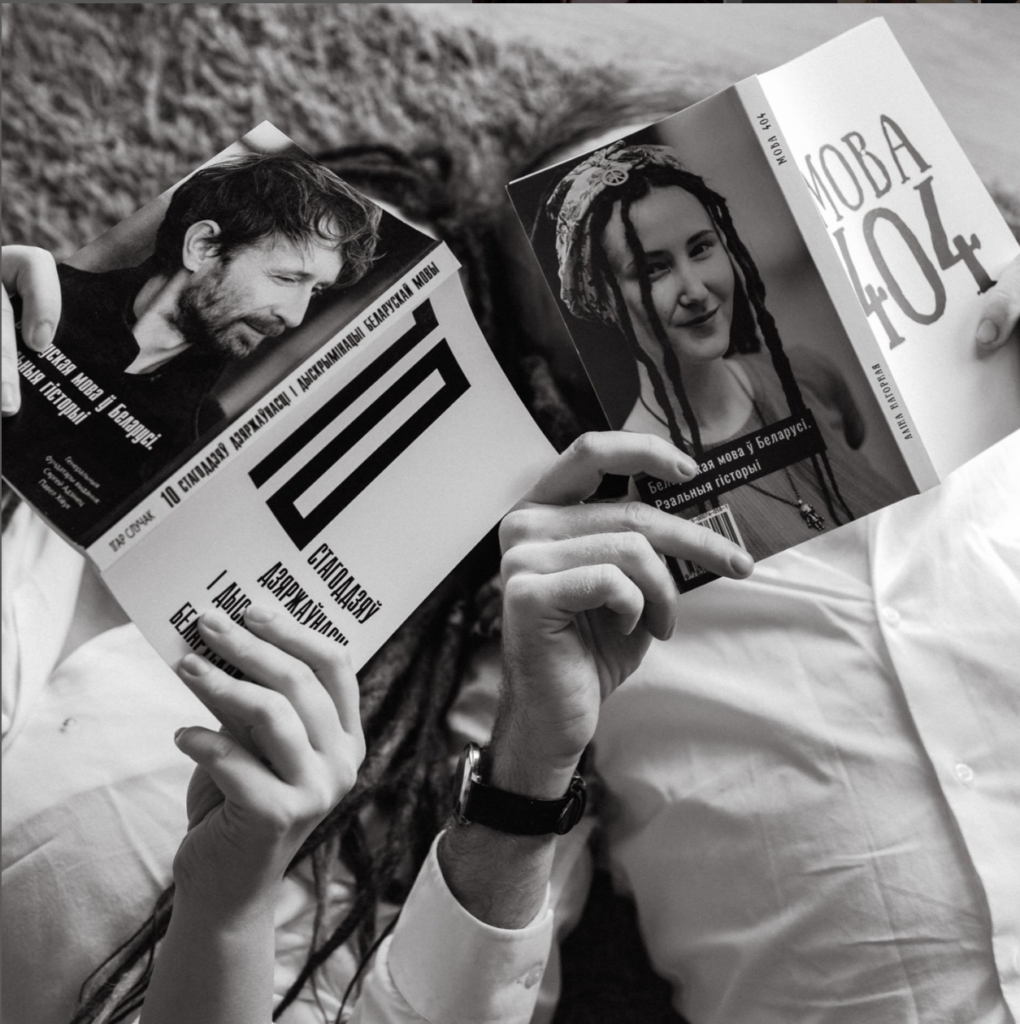

In her book MOVA 404, Alina Nahornaya sheds light on the struggles faced by ordinary Belarusians in exercising their fundamental right to use their native language. She uses the 404 “Not Found” error as a metaphor to illustrate how the Belarusian language is disappearing from different spheres of life and becoming increasingly marginalized within Belarusian society.

“Ten years ago, I began speaking Belarusian in my daily life, and it was a peculiar experience because everything in our country is geared towards Russian speakers. I didn’t have access to anything, including education or getting all sorts of information. Say, I go out into the city and want to find out which bus stop I need, it’s all in Russian. You don’t notice it as a Russian speaker, and it generally goes without saying that everyone knows Russian. But if you start paying attention to it, it can be quite challenging.”

Alina Nahornaya, language rights advocate.

“It’s obvious that speaking Russian isn’t something I’ve chosen for myself. This decision has been made for me, forced upon me. I never really thought about speaking Belarusian in Belarus before. I mean, there was just no one around me who spoke Belarusian, except for the language lessons at school. All the important stuff is in Russian and there’s no room for Belarusian at all. It exists, but you can’t really use it. But after meeting my future husband, Ihar, I realized the importance of language rights.”

He has focused on defending linguistic rights through legal channels, and it has yielded results. Until 2020, we started seeing some positive results, like sports posters in Belarusian, which was thanks to Ihar’s efforts. We even managed to change a few laws, which now seems hard to believe. The Belarusian language appeared on city signs. We created whole campaigns for this and had some great results in Homel, also in Baranovichi and a few other cities. It was just an idea I had, while I was thinking about ways to make Belarusian more visible to everyone.

“We faced a lot of hate, both from ordinary people and from officials. I might be out in the city and meet a city council member who would openly insult me right there on the street. Our efforts ended up annoying every Belarusian state institution. In other words, they were fed up with what we did,” Alina recalls.

When all the turmoil began in 2020, these wonderful institutions saw an opportunity to get back at us for all the trouble we’ve caused them over the years. They had to, and still have to, respond to our requests for things like translating their websites into Belarusian. They realized that they were now the ones who could make life difficult for us. At first, for half a year or maybe a bit longer, the police, the Investigative Committee, or just some strange people in a van would show up by our house every two weeks. Then it started happening more and more often. Those six months were incredibly stressful because I had a young child, and at some point I even stopped leaving the house. The men kept coming by and at some point they trespassed on our property – they broke into our yard. I knew it was only a matter of time before they would break into the house because they were getting really brazen. So, we left and started moving from place to place in Belarus. We became quite skilled at hiding, but after a while, we grew very tired of this life and made the decision to leave.

Why would a sovereign state try to limit the use of its own official language and discriminate against its speakers? The answers to this question can be found in the past.

The history of the Belarusian language is nothing short of extraordinary. It has weathered centuries of challenges to emerge as a symbol of resilience and cultural heritage. It has used three different alphabets during that time – Latin, Cyrillic and Arabic. In the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, a multinational medieval state, Old Belarusian played a pivotal role as the primary language of state documents, official correspondence and administrative records. But starting from the 17th century, Polish began to push Belarusian out of the state and cultural sphere. The 18th century brought further challenges as the Russian Empire annexed Belarusian land, which led to a decline of the Belarusian literary language. Despite this, the existing folk dialects managed to survive, preserving the essence of the language through the ages.

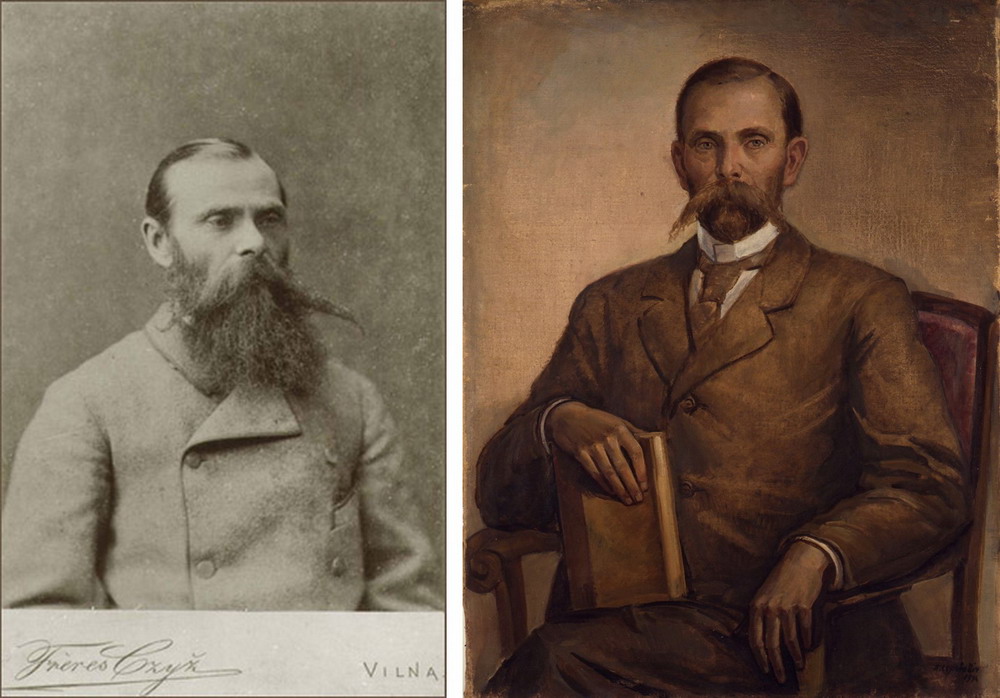

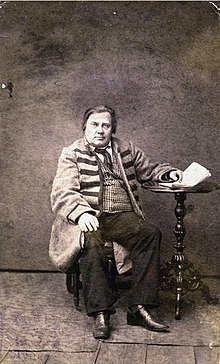

The Russian authorities fought against any manifestations of national identity, including bans on printing and teaching in Belarusian, but they were unable to stifle the emergence of new literature and cultural movements in Belarus. The playwright Vincent Dunin-Marcinkievič was the first to launch his literary career in Belarusian.

Around the same time, Francišak Bahuševič wrote the fundamental manifesto of the Belarusian national idea. Bahuševič is widely recognized as the pioneering writer of the Belarusian revival, whose poems served as both a program and an appeal. In the history of Belarusian national self-determination, they signify the onset of a new era.

The 20th century was a tumultuous time for Belarus, marked by war, occupation, Stalinist purges and the Soviet policy of promoting Russian at the expense of national languages. Despite these immense challenges, Belarus managed to undergo a remarkable transformation, ultimately emerging as a sovereign state.

The Belarusian Democratic Republic, BNR, which was proclaimed in March 1918 and only existed for less than a year, became a foundational and inspirational force in the quest for Belarusian national self-determination. Its governing body, the Rada BNR, has continued to work in exile from 1919, advocating for the advancement of Belarusian independence and democracy.

The late 1980s and the early 1990s marked a period of significant cultural and linguistic revival in Belarus. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Belarusian language experienced a resurgence, reclaiming its place in public life and the education system. This cultural renaissance was accompanied by a rise in national consciousness and a desire to embrace and celebrate Belarusian identity.

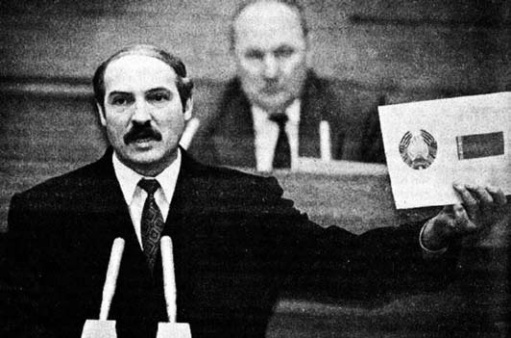

However, the revival did not last long. The political landscape in Belarus underwent a dramatic shift with Alexander Lukashenko coming to power in 1994. His administration adopted a narrative steeped in Soviet nostalgia. Belarusian became increasingly associated with oppositional voices and dissent.

“From the very beginning, Lukashenko based his political program on a certain nostalgia for the Soviet era, on downplaying the Soviet terror, the Soviet Russification, on trivializing the danger of it, on understating the tragedy of it, and that is why he ran for the parliament as a Russian-speaking candidate and then pursued the presidency as a Russian-speaking candidate. When in power, he very quickly picked up this Soviet policy of Russification, which had been ongoing for decades and had deeply tragic consequences for the Belarusian identity and language.”

Aleś Čajčyc, Rada BNR representative

He continued to implement this policy, with a crucial milestone in this process being the so-called referendum in 1995, which officially granted the Russian language the status of a state language. It had the status of an official language before that and was completely functional, but the Belarusian language had, let’s say, a kind of primacy, more “weight” as the only state language, even though no one was forbidden to use Russian.

“The referendum that granted Russian the status of a state language was of course illegitimate and falsified, much like any of the elections under Lukashenko’s rule. While Russian was declared the second state language, it effectively became the primary and sole state language,” Ales stresses.

As time went on, the situation deteriorated, leading to the gradual disappearance of the Belarusian language from various spheres of life, including education, state media, and government affairs. At present, the Belarusian state almost exclusively operates in Russian, accounting for about 95% of the total. The Belarusian language has found limited refuge in certain cultural, traditional and folklore contexts where it is still being used. However, practical and essential information is available only in Russian. It’s a fact. This situation is unique in Europe, as the state language of the country is marginalized by the sovereign state, or the nominally sovereign state. You won’t find it anywhere else.

Even before the peaceful protests in August 2020, using the Belarusian language in professional settings, academic institutions and other formal environments was not just uncommon but was often viewed as a form of political statement.

“Earlier I never really made an effort to learn Belarusian because I didn’t see the point. I mean, I can speak Russian, so why bother? But then I came to understand that it’s not a question of nationalism. Every language carries its own perspective, its own unique philosophy. That’s why I wanted to embrace my Belarusian identity, because it’s more a part of who I am as opposed to Russianness. And I figured, if I don’t start with myself, then how can I expect anything to change?”

Zmicier Karol, doctor, LGBT activist

So I decided to conduct an experiment to see if I could speak Belarusian, study in Belarusian, and eventually work as a Belarusian-speaking doctor. Of course, if you speak Belarusian, it becomes immediately apparent to others. And there is this difference: it was much less obvious that I was a member of the queer community, since I don’t have a very feminine appearance. However, when people found out that I was gay, […] most of them didn’t have any further questions about it; everything kind of clicked into place and they said, “Ah, okay.” However, when speaking Belarusian, I had to explain why I stand by this choice and why it carries political significance, even though I wasn’t involved in any political campaigns, rallies, or other political activity. The mere presence of a Belarusian-speaking doctor required justification – I needed to reassure people that it wasn’t dangerous, that it didn’t hinder my work or make it difficult for other doctors, and that I could effectively communicate with other medical professionals.

In the August 2020 elections, Lukashenko announced that he had received 80.1% of the votes. Belarusian society did not accept the results of the rigged election, leading to massive and prolonged protests. In response to the protests, Lukashenko’s regime used unprecedented force in repressing members of civil society. Thousands of people were arrested and hundreds of thousands were forced to flee the country.

Since August 2020, the Belarusian language has increasingly become the target of attacks by the Lukashenko regime. Alina Nahornaya’s survey reveals a troubling pattern of repression and censorship targeting anyone who embraces Belarusian. The act of communicating in Belarusian has transformed into an act of defiance, carrying the risk of persecution and arrest.

Belarusian books are being banned: even two poems by the Belarusian classic writer Vincent Dunin-Marcinkievič are now classified as “extremist”.

Despite the repression in Belarus, we are seeing an increase in demand for the Belarusian language both within the country and abroad. One of the key tasks of the Belarusian democratic forces in exile is to revitalize the Belarusian language, promoting its use in education, literature, publishing, music, cinema and other domains.

Following the downfall of Lukashenko’s regime, huge efforts will be needed to mend the damage caused by decades of dictatorial rule. A critical focus during this transition should be the reinstatement of the Belarusian language in all sectors of society.

Alina Nahornaya thinks that “Belarusian will do fine, since it has withstood a lot, both the Polish influence and the discrimination in favor of Russian, and it has stayed alive until now.” She finds it amazing how much mova has endured without going under. “I think that if every one of us understands that preserving the Belarusian language is an important endeavor for Belarus – in fact, I believe that that the foundation of Belarusian statehood lies in its language – so if everyone just makes a small contribution, the usage of the language will gradually expand in Belarus and it will become increasingly prevalent”, says Alina.

Belarusians are keenly aware of the challenges ahead and have not given up on their future: after all, the fourth-ranked word in the Belarusian Word of the Year ranking was nadzieja, which translates to “hope”.