“Until the very last moment, I could not believe that Kyiv would be bombed…”

Thousands of Belarusians, forced to flee the Lukashenko regime’s repression and find a new home in Ukraine, became refugees for the second time because of the Russia-Ukraine war. Vital is a representative of the “Country to Live in” social movement. His activism started with Siarhei Tsikhanouski’s electoral campaign.

“I collected signatures [for a presidential candidate] at the Kamarouski market in Minsk. I was near the Stela monument on August 9, 2020 [the primary presidential election day] and in the vicinity of Pushkinskaya subway station, where I was hit by a rubber bullet, on August 10. I saw the death of Aliaksandr Taraikouski [a peaceful protester killed by special forces on August 10, 2020]. After August 2020, we organized Zoom meetings with Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, first in Minsk and then in different cities. We published a protest newspaper called Real News and organized lectures on self-government. We distributed stickers, merchandise, and flyers and helped political prisoners.”

“In the fall of 2020, I was detained at a women’s march. At that time, the police didn’t figure out who I was and let me go by nightfall. I used to work in the judicial system, so I knew I would probably be fined. That’s exactly what happened. I didn’t pay the fine, although solidarity foundations offered to assist with it.”

Vital says that his acquaintances warned him about a criminal case against him:

“We had less than a day to pack up. I drove through the woods into Russia, then crossed the Russia-Ukraine border relatively easily. That’s because I moved during this period between when they started looking for me in Belarus but hadn’t yet prohibited me from traveling outside the country. My mother died a week after I had left. But I couldn’t go back to attend her funeral…”

“I’ve always felt comfortable in Ukraine, so I decided to stay. Plus, I didn’t have a visa to go any farther. I had already lived in Kyiv for more than six months in 2014. In Ukraine, I had no cultural or language barrier. I got legal status in Ukraine easily and started helping others: we established a foundation and helped active Belarusians register as volunteers, which was the basis for obtaining residence permits.”

Vital says that he had already been living in Kyiv for six months when the war began.

“Military training sessions organized by the Azov Regiment had been held in all Ukrainian cities since the fall of 2021. I saw that many people were preparing for war. We would meet with the guys who later established the Kastus Kalinouski Regiment in a bar. We were given lectures on what to do when the war breaks out: what medicines are needed and what groceries to buy first. But no one thought at the time that events would unravel on such a scale. Until the very last moment, we could not believe they would begin bombing Kyiv. Albeit, two or three days before the start of the war, we diligently purchased everything we needed and agreed to meet at our apartment in case of emergency.”

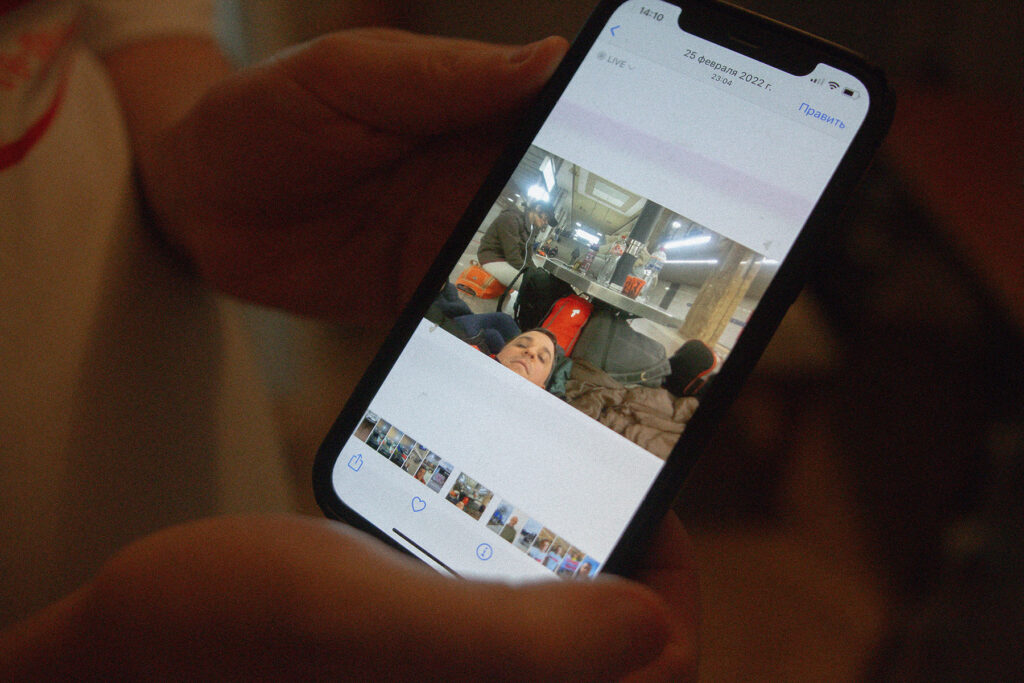

“On the morning of February 24, my neighbor woke me up: ‘It has started, they are bombing us!’ I had already heard it: we lived near Minskaya subway station, a stone’s throw from Irpin and Bucha. The rumbling sounds permeated the area. A couple of other people came over from different neighborhoods. An acquaintance from Vyshhorod told me a military base near his home had been bombed out. We went to a pharmacy. On my way there, I saw teenagers digging trenches. That’s when I realized that Kyiv would never be surrendered.”

“At first, we didn’t plan to leave. The reports that Kyiv was surrounded were the most frightening. We didn’t know the real situation. All we heard was that something exploded somewhere. A sabotage group broke through and was shot near our home. A sound of gun battle all around is quite an unpleasant experience, to put it mildly.”

“On the second or third day, we learned from Telegram channels that weapons were being distributed in Kyiv. We tried to pick up weapons three times: twice, they ran out of weapons by the time we got to the distribution points. We were among the first on the third attempt, but someone called the police on us because of our Belarusian passports. After a conversation, the police let us go, but we never received any weapons.”

“A week later, our group decided to try to leave, too. We didn’t have a car, but there were trains. The subway didn’t work, so we walked to the railway station. On our way there, we came across a firefight: there was nowhere to hide, so we just had to keep running.”

Vital realized that finding an apartment in bigger cities in Western Ukraine was impossible: the flow of refugees was too massive.

“When approaching Khmelnytskyi by train, we saw Zhmerynka station, and I suggested we get off. We found out that there was a refugee center in the town, so we went there. The Ukrainian Security Service (SBU) officers picked us up ten minutes later. They placed everyone in separate rooms and started interrogating us. After they found out who we were, they even apologized. The next day, we went to the local administration, saying we wanted to help. We weaved camouflage nets, made Molotov cocktails, and helped the territorial defense forces.”

“We had a good relationship with the locals. The only thing is that before the war, they thought Lukashenko was an alright dude and were completely unaware of the situation we had in Belarus: neither the mass protests nor torture in prisons. When I told them that one could go to jail for wearing clothing of certain colors in Belarus, people couldn’t believe it.”

Vital lived in Zhmerynka until mid-April. When he realized he was no longer helpful in Ukraine, he decided to go to Poland.

“The Poles took me in for a talk and checked my phone: they looked at photos and notes. Yet, I didn’t experience any particular problems: I was already in Warsaw in the morning. After spending a week in Poland, I wanted to return to Ukraine. I bought a ticket but was made to disembark the bus. I decided it was a sign, and I had to stay in Warsaw for the time being.”

Vital admits that he does not feel comfortable in Poland.

“My adaptation here was difficult: the language and social structure are different, and the Polish way of life is peculiar. I don’t feel comfortable here: I haven’t learned Polish and don’t want to live in Poland forever, even though I found a decent job as a polygraph examiner in a Ukrainian company.”

Vital is acutely aware that his plans for the future depend on how the situation unfolds.

“I want to go back to Belarus as soon as possible. And I will do everything I can to speed up this process. I have high hopes for 2023. At the very least, I plan to go back to Kyiv in the second half of 2023.”

“I am sure that Ukraine will win this war. The question is how long it will take and at what cost the victory will be achieved. I don’t think Lukashenko will last long without Russian support, neither in the economic nor military aspects.”